In Bhaktapur Durbar Square, one bell shouts for attention while another whispers a secret. Beside the majestic Vatsala Temple sits the खिचा ख्व गाँ (Khicā Khva Gāṃ)—the “Barking Bell.”

This silent, damaged relic holds a story where royal nightmares, canine legends, and an astrological cure collide.

Chapter 1: The Legend of The Barking Bell

When the Bell Rings, the Dogs Cry

The popular legend is as charming as it is bizarre. It’s said that whenever the bell was rung, it emitted a high-frequency sound imperceptible to most humans but perfectly tuned to the canine residents of Bhaktapur.

The result wasn’t joyful barking, but a chorus of distressed whines and howls—as if the Dogs of Bhaktapur were collectively crying.

Its Newari name, खिचा ख्व गाँ (Khicā Khva Gāṃ), which directly translates to “the bell that makes dogs bark/cry” (‘Khicha’ relating to a dog’s cry, ‘Khva’ for bell), shows how its legendary characteristic was embedded into its identity from the very beginning

Chapter 2: The History

A King’s Nightmare and an Astrological Prescription

The bell’s true origin moves us from folklore to the royal court. Historical documentation confirms that the great builder-king Bhupatindra Malla installed this specific bell as part of the Vatsala Temple complex.

According to these records, the king was suffering from persistent nightmares or a perceived dosh (astrological flaw). Seeking a remedy, he consulted his jyotish (royal astrologer).

The prescribed solution was to cast and consecrate a specific bell at the temple site as a yantra—a ritual instrument for spiritual protection.

The bell, therefore, served a deeply personal function for the monarch’s peace of mind, rather than a public ceremonial purpose.

Its placement beside Vatsala, a goddess associated with protection, adds another layer of sacred intent to its installation.

Chapter 3: The Earthquake and The Bell’s Current Fate

The bell’s story took a tragic turn in the 2015 earthquakes. As detailed in reconstruction reports, the collapse of the Vatsala Temple caused severe damage to the Barking Bell.

Once a consecrated yantra installed to calm a king’s mind, it was left damaged and displaced—a silent and poignant relic of both its legendary past and the temple’s destruction.

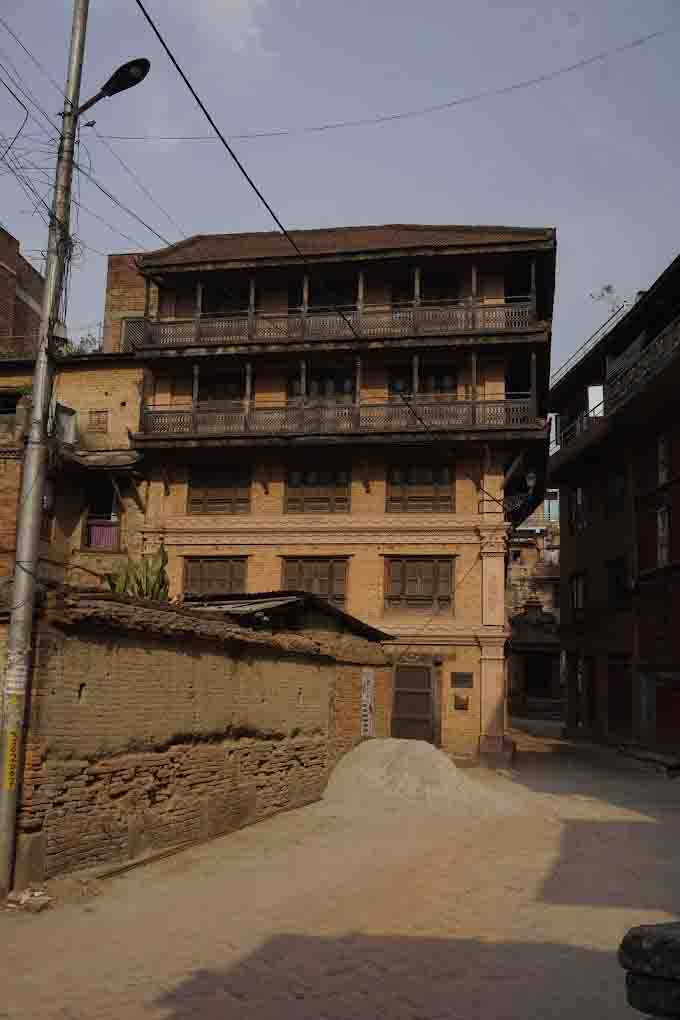

Today, it no longer hangs in its original, purposeful position. Visitors can find it sitting forlornly in a corner near the entrance to Mul Chowk.

Its current state serves as a tangible reminder of the fragility of heritage and the ongoing story of recovery and preservation in the Kathmandu Valley, directly linking to the documented “Vatsala Temple earthquake damage 2015.”

Why This Hidden Heritage Matters

The Barking Bell is a masterclass in Nepali heritage. It shows how a single artifact can operate on multiple levels:

- The Historical: A documented object from Bhupatindra Malla’s reign, detailed in official records.

- The Ritualistic: A prescribed astrological remedy for royalty, installed as a protective yantra.

- The Folkloric: A community-generated legend born from observable phenomena, so potent it became the bell’s name.

- The Contemporary: A symbol of loss and resilience after the 2015 earthquakes.

It reminds us that culture is built not just on kings and gods, but on the intersection of royal decree, priestly advice, and the imaginative interpretation of the people.

How to Visit & What to Feel

📍 Location: Bhaktapur Durbar Square, formerly adjacent to the Vatsala Temple, now placed near the entrance to Mul Chowk.

🕵️ How to Find: Look for a solitary, ancient-looking bronze bell sitting in a corner, not hanging in its original glory.

📖 The Moment: You will not hear it ring. Its inauspicious reputation and damaged state ensure its silence. But stand before it. Contemplate King Bhupatindra Malla seeking solace from his dreams, the centuries of legend it inspired, and the catastrophic event that left it here. It’s a small bell with a layered, profound story.

Challenge for Visitors: Can you find where the Barking Bell sits today?

Take a photo of its current spot near Mul Chowk and tag us @adayinnepal with #FoundTheBarkingBell.

We’ll share the best finds!

A Parting Thought

Bhaktapur Durbar Square is a symphony of power and devotion. The Barking Bell—खिचा ख्व गाँ—is its most mysterious and human note.

It wasn’t made for glory or loud announcements. It was made to quiet a king’s troubled mind, sparked a legend that echoed through alleyways, and survived a disaster to tell its tale.

This is the soul of Nepali culture: deeply personal, unexpectedly poetic, and waiting quietly for those who look beyond the obvious.

For Further Reading:

The historical and architectural context of the Vatsala Temple and its bell is detailed in the official publication “नृत्य वत्सला मन्दिर पुनः निर्माण २०७८” (Reconstruction of Nritya Vatsala Temple) by Bhaktapur Municipality.